Greater Manchester

| Greater Manchester | |

|---|---|

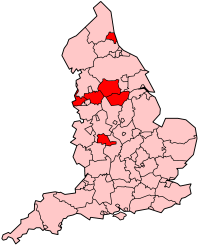

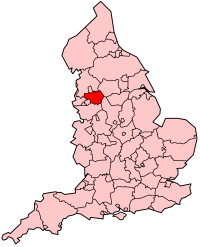

Shown within England |

|

| Geography | |

| Status | Metropolitan county & Ceremonial county |

| Origin | 1 April 1974[1] (Local Government Act 1972) |

| Region | North West England |

| Area - Total |

Ranked 39th 1,276 km2 (493 sq mi) |

| ONS code | 2A |

| NUTS 2 | UKD3 |

| Demography | |

| Population - Total (2008) - Density |

Ranked 3rd 2,573,200 2,016 /km2 (5,220 /sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | 88.9% White 6.5% S.Asian 1.7% Black 1.6% Mixed Race 1.3% E. Asian and Other |

| Politics | |

| Greater Manchester County Council (1974–1986) Greater Manchester Combined Authority (from 2011) |

|

| Executive | |

| Members of Parliament |

List of Greater Manchester MPs |

| Metropolitan Boroughs | |

|

|

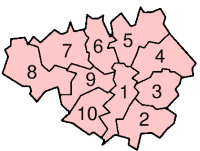

Greater Manchester is a metropolitan county in North West England, with a population of 2.57 million. It encompasses one of the largest metropolitan areas in the United Kingdom and comprises ten metropolitan boroughs: Bolton, Bury, Oldham, Rochdale, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford, Wigan, and the cities of Manchester and Salford. Greater Manchester was created on 1 April 1974 as a result of the Local Government Act 1972.

Greater Manchester spans 496 square miles (1,285 km2).[2] It is landlocked and borders Cheshire (to the south-west and south), Derbyshire (to the south-east), West Yorkshire (to the north-east), Lancashire (to the north) and Merseyside (to the west). There is a mix of high density urban areas, suburbs, semi-rural and rural locations in Greater Manchester, but overwhelmingly the land use is urban. It has a focussed central business district, formed by Manchester city centre and the adjoining parts of Salford and Trafford, but Greater Manchester is also a polycentric county with ten metropolitan districts, each of which has at least one major town centre and outlying suburbs. The Greater Manchester Urban Area is the third most populous conurbation in the UK, and spans across most of the county's territory.

For the 12 years following 1974 the county had a two-tier system of local government; district councils shared power with the Greater Manchester County Council. The county council was abolished in 1986, and so its districts (the metropolitan boroughs) are now effectively unitary authority areas. However, the metropolitan county continues to exist in law and as a geographic frame of reference,[3] and several county-wide services are co-ordinated through the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities. Greater Manchester is coterminous with the Manchester City Region, a pilot subdivision of England to be administered by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority from April 2011. As a ceremonial county, Greater Manchester has a Lord Lieutenant and a High Sheriff.

Before the creation of the metropolitan county, the name SELNEC was used for the area, taken from the initials of "South East Lancashire North East Cheshire". Greater Manchester is an amalgamation of 70 former local government districts from the former administrative counties of Lancashire, Cheshire and Yorkshire, West Riding and eight independent county boroughs.[4]

Contents |

History

Origins

Although the modern county of Greater Manchester was not created until 1974, the history of its constituent settlements and parts goes back centuries. There is evidence of Iron Age inhabitation, particularly at Mellor,[5] and Celtic activity in a settlement named Chochion, believed to have been an area of Wigan settled by the Brigantes.[6] Stretford was also part of the land believed to have been occupied by the Celtic Brigantes tribe, and lay on their border with the Cornovii on the southern side of the River Mersey.[7] The remains of 1st century forts at Castlefield in Manchester,[8] and Castleshaw Roman fort in Saddleworth,[9] are evidence of Roman occupation. Much of the region was omitted from the Domesday Book of 1086; Redhead states that this was because only a partial survey was taken, rather than sparsity of population.[10]

During the Middle Ages, much of what became Greater Manchester lay within the hundred of Salfordshire – an ancient division of the county of Lancashire. Salfordshire encompassed several parishes and townships, some of which, like Rochdale, were important market towns and centres of England's woollen trade. The development of what became Greater Manchester is attributed to a shared tradition of domestic flannel and fustian cloth production, which encouraged a system of cross-regional trade.[11][12][13] The Industrial Revolution transformed the local domestic system, and much of Greater Manchester's heritage is related to textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution and the infrastructure that grew up to support this sector.[13] The townships in and around Manchester began expanding "at an astonishing rate" around the turn of the 19th century as part of a process of unplanned urbanisation brought on by a boom in textile processing.[14] Places such as Bury, Oldham and Bolton played a central economic role in the nation, and by the end of the 19th century had become some of the most important and productive mill towns in the world.[15] However, it was Manchester that was the most populous settlement, a major city and the world's largest marketplace for cotton goods.[16][17] By 1835 "Manchester was without challenge the first and greatest industrial city in the world",[17] and due to its commercial and socioeconomic success the need for local government and geo-administrative reform for the region in and around the city was proposed in as early as the 1910s.[18]

By the 18th century, traders from Germany had coined the name Manchesterthum, meaning "Greater Manchester", and were using that as a name for the region in and around Manchester.[19] However, the English term "Greater Manchester" did not appear until the start of the 20th century. One of its first known recorded uses was in a 1914 report put forward in response to what was considered to have been the successful creation of the County of London in 1889. The report suggested that a county should be set up to recognise the "Manchester known in commerce", and referred to the areas that formed "a substantial part of South Lancashire and part of Cheshire, comprising all municipal boroughs and minor authorities within a radius of eight or nine miles of Manchester".[18][20] In his 1915 book Cities In Evolution, innovative urban planner Sir Patrick Geddes wrote "far more than Lancashire realises, is growing up another Greater London".[21]

.png)

Conurbations in England tend to build-up at the historic county boundaries[22] and Greater Manchester is no exception. Most of Greater Manchester lay within the ancient county boundaries of Lancashire; those areas south of the Mersey and Tame were in Cheshire. The Saddleworth area and a small part of Mossley are historically part of Yorkshire and in the south-east a small part in Derbyshire. The areas that were incorporated into Greater Manchester in 1974 previously formed parts of the administrative counties of Cheshire, Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire and of eight independent county boroughs.[4] By the early 1970s, this system of demarcation was described as "archaic" and "grossly inadequate to keep pace both with the impact of motor travel, and with the huge increases in local government responsibilities".[23]

The Manchester Evening Chronicle brought to the fore the issue of "regional unity" for the area in April 1935 under the headline "Greater Manchester – The Ratepayers' Salvation". It reported on the "increasing demands for the exploration of the possibilities of a greater merger of public services throughout Manchester and the surrounding municipalities".[24] The issue was frequently discussed by civic leaders in the area at that time, particularly those from Manchester and Salford. The Mayor of Salford pledged his support to the idea, stating that he looked forward to the day when "there would be a merging of the essential services of Manchester, Salford, and the surrounding districts constituting Greater Manchester."[24] Proposals were halted by the Second World War, though in the decade after it, the pace of proposals for local government reform for the area quickened.[25] In 1947, Lancashire County Council proposed a three "ridings" system to meet the changing needs of the county of Lancashire, including those for Manchester and surrounding districts.[25] Other proposals included the creation of a Manchester County Council, a directly elected regional body. In 1951, the census in the UK began reporting on South East Lancashire as a homogeneous conurbation.[25]

Redcliffe-Maud Report

The Local Government Act 1958 designated the south east Lancashire area (which, despite its name, included part of north east Cheshire), a Special Review Area. The Local Government Commission for England presented draft recommendations, in December 1965, proposing a new county based on the conurbation surrounding and including Manchester, with nine most-purpose boroughs corresponding to the modern Greater Manchester boroughs (excluding Wigan). The review was abolished in favour of the Royal Commission on Local Government before issuing a final report.[26]

The Royal Commission's 1969 report, known as the Redcliffe-Maud Report, proposed the removal of much of the then existing system of local government. The commission described the system of administering urban and rural districts separately as outdated, noting that urban areas provided employment and services for rural dwellers, and open countryside was used by town dwellers for recreation. The commission considered interdependence of areas at many levels, including travel-to-work, provision of services, and which local newspapers were read, before proposing a new administrative metropolitan area.[27] The area had roughly the same northern boundary as today's Greater Manchester (though included Rossendale), but covered much more territory from Cheshire (including Macclesfield, Warrington, Alderley Edge, Northwich, Middlewich, Wilmslow and Lymm), and Derbyshire (the towns of New Mills, Whaley Bridge, Glossop and Chapel-en-le-Frith – a minority report suggested that Buxton be included).[28] The metropolitan area was to be divided into nine metropolitan districts, based on Wigan, Bolton, Bury/Rochdale, Warrington, Manchester (including Salford and Old Trafford), Oldham, Altrincham, Stockport and Tameside.[28] The report noted "The choice even of a label of convenience for this metropolitan area is difficult".[29] Seven years earlier, a survey prepared for the British Association intended to define the "South-East Lancashire conurbation" noted that "Greater Manchester it is not ... One of its main characteristics is the marked individuality of its towns, ... all of which have an industrial and commercial history of more than local significance".[30] The term Selnec (or SELNEC) was already in use as an abbreviation for south east Lancashire and north east Cheshire; Redcliffe-Maud took this as "the most convenient term available", having modified it to south east Lancashire, north east and central Cheshire.[28] Following the Transport Act 1968, in 1969 the SELNEC Passenger Transport Executive (an authority to co-ordinate and operate public transport in the region) was set up, covering an area smaller than the proposed Selnec, and different again to the eventual Greater Manchester. Compared with the Redcliffe-Maud area, it excluded Macclesfield, Warrington, and Knutsford but included Glossop and Saddleworth in the West Riding of Yorkshire. It excluded Wigan, which was in both the Redcliffe-Maud area and in the eventual Greater Manchester (but had not been part of the 1958 act's review area).[31]

Redcliffe-Maud's recommendations were accepted by the Labour-controlled Government in February 1970.[32] Although the Redcliffe-Maud Report was rejected by the Conservative government after the 1970 general election, there was a commitment to local government reform, and the need for a metropolitan county centred on the conurbation surrounding Manchester was accepted. The new government's original proposal was much smaller than the Redcliffe-Maud Report's Selnec, with areas such as Warrington, Winsford, Northwich, Knutsford, Macclesfield and Glossop retained by their original counties to ensure their county councils had enough revenue to remain competitive (Cheshire County Council would have ceased to exist).[32] Other late changes included the separation of the proposed Bury/Rochdale authority (retained from the Redcliffe-Maud report) into the Metropolitan Borough of Bury and the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale. Bury and Rochdale were originally planned to form a single district (dubbed "Botchdale" by local MP Michael Fidler)[33][34] but were divided into separate boroughs. To re-balance the districts, the borough of Rochdale took Middleton from Oldham.[35] During the passage of the bill, the towns of Whitworth, Wilmslow and Poynton successfully objected to their incorporation in the new county.[32]

| post-1974[36] | pre-1974 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan county | Metropolitan borough | County boroughs | Non-county boroughs | Urban districts | Rural districts |

.png) |

Bury | Bury | Prestwich • Radcliffe • | Ramsbottom • Tottington • Whitefield | |

| Bolton | Bolton | Farnworth | Blackrod • Horwich • Kearsley • Little Lever • Turton • Westhoughton | ||

| Manchester | Manchester | Ringway[37] | |||

| Oldham | Oldham | Chadderton • Crompton • Failsworth • Lees • Royton • Saddleworth | |||

| Rochdale | Rochdale | Middleton • Heywood • | Littleborough • Milnrow • Wardle | ||

| Salford | Salford | Eccles • Swinton and Pendlebury | Irlam • Worsley | ||

| Stockport | Stockport | Bredbury and Romiley • Cheadle and Gatley • Hazel Grove and Bramhall • Marple | |||

| Tameside | Ashton-under-Lyne • Dukinfield • Hyde • Mossley • Stalybridge | Audenshaw • Denton • Droylsden • Longendale | |||

| Trafford | Altrincham • Sale • Stretford | Bowdon • Hale • Urmston | Bucklow | ||

| Wigan | Wigan | Leigh | Abram • Ashton in Makerfield • Aspull • Atherton • Billinge and Winstanley • Hindley • Ince-in-Makerfield • Golborne • Orrell • Standish-with-Langtree • Tyldesley | Wigan | |

1974–1997

.jpg)

The Local Government Act 1972 reformed local government in England by creating a system of two-tier metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties and districts throughout the country.[36] The act formally established Greater Manchester on 1 April 1974, although Greater Manchester County Council (GMCC) had been running since elections in 1973.[38] The leading article in The Times on the day the Local Government Act came into effect noted that the "new arrangement is a compromise which seeks to reconcile familiar geography which commands a certain amount of affection and loyalty, with the scale of operations on which modern planning methods can work effectively".[39] Frangopulo noted that the creation of Greater Manchester "was the official unifying of a region which, through history and tradition, had forged for itself over many centuries bonds ... between the communities of town and village, each of which was the embodiment of the character of this region".[40] The name Greater Manchester was decided by Her Majesty's Government, having been favoured over Selnec by the local population.[41]

By January 1974, a joint working party representing Greater Manchester had drawn up its county Structure Plan, ready for implementation by the Greater Manchester County Council. The plan set out strategic and long-term objectives for the forthcoming metropolitan county.[42] The highest priority was to increase the quality of life for its inhabitants by way of improving the county's physical environment and cultural facilities which had suffered following deindustrialisation—much of Greater Manchester's basic infrastructure dated from its 19th century industrial growth, and was unsuited to modern communication systems and life-styles.[43] Other objectives were to reverse the trend of depopulation in central-Greater Manchester, to invest in the county's country parks to improve the region's poor reputation on leisure and recreational facilities, and to improve the county's transport infrastructure and journey to work patterns.[44]

Because of political objection, particularly from Cheshire, Greater Manchester covered only the inner, urban 62 of the 90 former districts that the Royal Commission had outlined as an effective administrative metropolitan area.[45] In this capacity, GMCC found itself "planning for an arbitrary metropolitan area ... abruptly truncated to the south", and so had to negotiate several land-use, transport and housing projects with its neighbouring county councils.[45] However a "major programme of environmental action" by GMCC broadly succeeded in reversing social deprevation in its inner city slums.[45] Leisure and recreational successes included the Greater Manchester Exhibition Centre (better known as the G-Mex centre and now branded Manchester Central), a converted former railway station in Manchester city centre used for cultural events,[46] and GMCC's creation of five new country parks within its boundaries.[47]

Unlike most other modern counties (including Merseyside and Tyne and Wear), Greater Manchester was never adopted as a postal county by the Royal Mail. A review in 1973 noted that "Greater Manchester" would be unlikely to be adopted because of confusion with the Manchester post town.[48] And so the component areas of Greater Manchester held on to their pre-1974 postal counties until 1996, when they were abolished.[49]

A decade after they were established, the mostly Labour-controlled metropolitan county councils and the Greater London Council (GLC) had several high profile clashes with the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher, with regards overspending and high rates charging. Government policy on the issue was considered throughout 1982, and the Conservative Party put a "promise to scrap the metropolitan county councils" and the GLC, in their manifesto for the 1983 general election.[50][51] Greater Manchester County Council was abolished on 31 March 1986 under the Local Government Act 1985. That the metropolitan county councils were controlled by the Labour Party led to accusations that their abolition was motivated by party politics:[50] the general secretary of the National Association of Local Government Officers described it as a "completely cynical manoeuvre".[52] Most of the functions of GMCC were devolved to the ten Greater Manchester metropolitan district councils, though some functions such as emergency services and public transport were taken over by joint boards and continued to be run on a county-wide basis.[53] The Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (AGMA) was established to continue much of the county-wide services of the county council.[54] The metropolitan county continues to exist in law, and as a geographic frame of reference,[3] for example as a NUTS 2 administrative division for statistical purposes within the European Union.[55] Although having been a Lieutenancy area since 1974, Greater Manchester was included as a ceremonial county by the Lieutenancies Act 1997 on 1 July 1997.[56]

City Region

In 1998, the people of Greater London voted in a referendum in favour of establishing a new Greater London Authority, with mayor and an elected chamber for the county.[57] The New Local Government Network proposed the creation of a new Manchester City Region based on Greater Manchester and other metropolitan counties as part of on-going reform efforts, while a report released by the Institute for Public Policy Research's Centre for Cities has proposed the creation of two large city regions based on Manchester and Birmingham. In July 2007, The Treasury published its Review of sub-national economic development and regeneration, which stated that the government would allow those city regions that wished to work together to form a statutory framework for city regional activity, including powers over transport, skills, planning and economic development.[58] In January 2008, AGMA suggested that a formal government structure be created to cover Greater Manchester.[59] The issue resurfaced in June 2008 with regards to proposed congestion charging in Greater Manchester; Sir Richard Leese (leader of Manchester City Council) said "I've come to the conclusion that [a referendum on congestion charging should be held] because we don't have an indirectly or directly elected body for Greater Manchester that has the power to make this decision".[60] On 14 July 2008 the ten local authorities in Greater Manchester agreed to a strategic and integrated cross-county Multi-Area Agreement; a voluntary initiative aimed at making district councils "work together to challenge the artificial limits of boundaries" in return for greater autonomy from "Whitehall".[61] A referendum on the Greater Manchester Transport Innovation Fund was held in December 2008,[62] in which voters "overwhelmingly rejected" plans for public transport improvements linked to a peak-time weekday-only congestion charge.[63]

Following a bid from AGMA highlighting the potential benefits in combatting the financial crisis of 2007–2010, it was announced in the 2009 United Kingdom Budget that Greater Manchester and the Leeds City Region would be awarded Statutory City Region Pilot status, allowing (if they desired) for their constituent district councils to pool resources and become statutory Combined Authorities with powers comparable to the Greater London Authority.[64] The aim of the pilot is to evaluate the contributions to economic growth and sustainable development by Combined Authorities.[65] The Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 enabled the creation of a Combined Authority for Greater Manchester with devolved powers on public transport, skills, housing, regeneration, waste management, carbon neutrality and planning permission, pending approval from the ten councils.[64][66] Such strategic matters would be decided on via an enhanced majority rule voting system involving ten members appointed from among the councillors of the ten metropolitan boroughs (one representing each borough of Greater Manchester with each council also nominating one substitute) without the input of the UK's central government. The Transport for Greater Manchester Committee will be formed from a pool of 33 councillors allocated by council population (roughly one councillor for every 75,000 residents) to scrutinise the running of transport bodies and their finances, approve the decisions and policies of said bodies and form strategic policy recommendations or projects for the approval of the ten member panel.[64] The ten district councils of Greater Manchester approved the creation of the Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA) on 29 March 2010, and submitted its final recommendations for its constitution to the Department for Communities and Local Government and the Department for Transport. On 31 March 2010 the Communities Secretary John Denham approved the constitution and launched a 15 week public consultation on the draft bill together with the approved constitution.[67] The Association of Greater Manchester Authorities, which would be replaced by the GMCA, has requested that the new authority should be created as from April 1, 2011.[68][69][70]

Geography

Greater Manchester is a landlocked county spanning 492.7 square miles (1,276 km²). The Pennines rise along the eastern side of the county, through parts of Oldham, Rochdale and Tameside. The West Pennine Moors, as well as a number of coalfields (mainly sandstones and shales) lie in the west of the county. The rivers Mersey and Tame run through the county boundaries, both of which rise in the Pennines. Other rivers run through the county, including the Beal, the Douglas and the Irk. Black Chew Head is the highest point in Greater Manchester, rising 1,778 feet (542 m) above sea-level, within the parish of Saddleworth.[71] Chat Moss at 10.6 square miles (27 km2) comprises the largest area of prime farmland in Greater Manchester and contains the largest block of semi-natural woodland in the county.[72]

There is a mix of high density urban areas, suburbs, semi-rural and rural locations in Greater Manchester, but overwhelmingly the land use in the county is urban.[73] It has a strong regional central business district, formed by Manchester city centre and the adjoining parts of Salford and Trafford. However, Greater Manchester is also a polycentric county with ten metropolitan districts,[73] each of which has a major town centre – and in some cases more than one – and many smaller settlements. Greater Manchester is arguably the most complex urban area in the UK outside London,[73] and this is reflected in the density of its transport network and the scale of its needs for investment to meet the growing and diverse movement demands generated by its development pattern.

The table below outlines many of the county's settlements, and is formatted according to their metropolitan borough.

| Metropolitan county | Metropolitan borough | Centre of administration | Other components | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Manchester | Bury | Bury | Prestwich, Radcliffe, Ramsbottom, Tottington, Whitefield | |

| Bolton | Bolton | Blackrod, Farnworth, Horwich, Kearsley, Little Lever, South Turton, Westhoughton | ||

| Manchester | Manchester | Blackley, Cheetham Hill, Chorlton-cum-Hardy, Didsbury, Ringway, Withington, Wythenshawe | ||

| Oldham | Oldham | Chadderton, Shaw and Crompton, Failsworth, Lees, Royton, Saddleworth | ||

| Rochdale | Rochdale | Heywood, Littleborough, Middleton, Milnrow, Newhey, Wardle | ||

| Salford | Swinton | Eccles, Clifton, Little Hulton, Walkden, Worsley, Salford, Irlam, Pendlebury, Cadishead, Patricroft, Monton | ||

| Stockport | Stockport | Bramhall, Bredbury, Cheadle, Gatley, Hazel Grove, Marple, Romiley Woodley | ||

| Tameside | Ashton-under-Lyne | Audenshaw, Denton, Droylsden, Dukinfield, Hyde, Longdendale, Mossley, Stalybridge | ||

| Trafford | Stretford | Altrincham, Bowdon, Hale, Sale, Urmston | ||

| Wigan | Wigan | Abram, Ashton-in-Makerfield, Aspull, Astley, Atherton, Bryn, Golborne, Higher End, Hindley, Ince-in-Makerfield, Leigh, Orrell, Shevington, Standish, Tyldesley, Winstanley | ||

The Greater Manchester Urban Area is an area of land defined by the Office for National Statistics consisting of the large conurbation surrounding and including the City of Manchester. Its territory spans much, but not all of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester. It excludes settlements such as Wigan and Marple from within the Greater Manchester county boundaries, but includes some settlements which are outside of the county boundaries, such as Wilmslow and Alderley Edge in Cheshire, and Whitworth in Lancashire. Although neither the Greater Manchester county, nor the Greater Manchester Urban Area have been granted city status in the United Kingdom, European Union literature suggests that the conurbation surrounding Manchester constitutes a homogonous urban city region.[74]

Climate

Greater Manchester experiences a temperate maritime climate, like most of the British Isles, with relatively cool summers and mild winters. The county's average annual rainfall is 806.6 millimetres (31.76 in)[75] compared to the UK average of 1,125.0 millimetres (44.29 in),[76] and its mean rain days are 140.4 mm (5.53 in) per annum,[75] compared to the UK average of 154.4 mm (6.08 in).[76] The mean temperature is slightly above average for the United Kingdom.[77] Greater Manchester also has a relatively high humidity level, which lent itself to the optimised and breakage-free textile manufacturing which took place around the county. Snowfall is not a common sight in the built up areas, due to the urban warming effect. However, the Pennine and Rossendale Forest hills around the eastern and northern edges of the county receive more snow, and roads leading out of the county can be closed due to heavy snowfall,[78] notably the A62 road via Standedge, the A57 (Snake Pass) towards Sheffield,[79] and the M62 over Saddleworth Moor. In the most southern point of Greater Manchester, Woodford's Met Office weather station recorded a temperature of −17.6 °C (0 °F) on 8 January 2010, during the Winter of 2009-2010 in the United Kingdom.[80]

| Climate data for Manchester | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.9 (48) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.7 (56.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

12.75 (54.95) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.3 (45.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.0 (50) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.15 (43.07) |

| Rainfall mm (inches) | 69 (2.72) |

50 (1.97) |

61 (2.4) |

51 (2.01) |

61 (2.4) |

67 (2.64) |

65 (2.56) |

79 (3.11) |

74 (2.91) |

77 (3.03) |

78 (3.07) |

78 (3.07) |

810 (31.89) |

| Avg. rainy days | 18.2 | 13.1 | 15.6 | 14.4 | 15.1 | 14.4 | 13.6 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 16.5 | 17.0 | 17.4 | 185.3 |

| Source: Worldweather.org taken between 1971 and 2000 at the Met Office weather station at Manchester Airport. | |||||||||||||

Governance

Greater Manchester is divided into 28 parliamentary constituencies – 18 borough constituencies and 10 county constituencies. Most of Greater Manchester is controlled by the Labour party, and is generally considered a Labour stronghold,[81][82] with only four constituencies (since the 2005 General Election) belonging to the Liberal Democrats, and one constituency to the Conservative party. Local governance in Greater Manchester is currently provided by the councils of ten districts, known as metropolitan boroughs, these are: Bolton, Bury, the City of Manchester, Oldham, Rochdale, the City of Salford, Stockport, Tameside, Trafford and Wigan.

Eight of the ten metropolitan boroughs of Greater Manchester are named after the eight former county boroughs that now compose the largest centres of population and greater historical and political prominence.[83] As an example, the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport is centred on the town of Stockport, a former county borough, but includes other smaller settlements, such as Cheadle, Gatley, and Bramhall.[83] The names of two of the metropolitan boroughs were given a neutral name because, at the time they were created, there was no agreement on the town to be put forward as the administrative centre and neither had a county borough. These boroughs are Tameside and Trafford, centred on Ashton-under-Lyne and Stretford, respectively, and are named with reference to geographical and historical origins.[83]

For the first 12 years after the county was created in 1974, the county had a two-tier system of local government, and the metropolitan borough councils shared power with the Greater Manchester County Council.[84] The Greater Manchester County Council, a strategic authority running regional services such as transport, strategic planning, emergency services and waste disposal, comprised 106 members drawn from the ten metropolitan boroughs of Greater Manchester.[85] However in 1986, along with the five other metropolitan county councils and the Greater London Council, the Greater Manchester County Council was abolished, and most of its powers were devolved to the boroughs.[84] Various civil parishes exist in certain parts of Greater Manchester.

Although the county council, which was based in what is now Westminster House off Piccadilly Gardens, has been abolished, a number of local government functions take place at the county level. That eight of the ten borough councils have (for the most part) been Labour-controlled since 1986, has helped maintain informal co-operation between the districts at a county-level.[45] However, the ten authorities of Greater Manchester co-operate formally through the Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (AGMA), which meets to create a co-ordinated county-wide approach to many issues. The AGMA funds some county-wide bodies such as the Greater Manchester County Record Office. Through the AGMA, the ten authorities of Greater Manchester co-operate on many policy issues, including county-wide Local Transport Plans.[86] Some local services are provided county-wide, administered by statutory joint boards. These are Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive, (GMPTE) which is responsible for planning and co-ordinating public transport across the county; the Greater Manchester Police, who are overseen by a joint Police authority; the Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, who are administered by a joint "Fire and Rescue Authority"; and the Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority. These joint boards are made up of councillors appointed from each of the ten boroughs (except the Waste Disposal Authority, which does not include the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan). The ten boroughs jointly own the Manchester Airport Group which controls Manchester Airport and three other UK airports. Other services are directly funded and managed by the local councils.[87]

Greater Manchester is a ceremonial county with its own Lord-Lieutenant who is the personal representative of the monarch. The Local Government Act 1972 provided that the whole of the area to be covered by the new metropolitan county of Greater Manchester would also be included in the Duchy of Lancaster – extending the duchy to include areas which were formerly in the counties of Cheshire and the West Riding of Yorkshire. Until 31 March 2005, Greater Manchester's Keeper of the Rolls was appointed by the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster; they are now appointed by the Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain.[88] The first Lord Lieutenant of Greater Manchester was Sir William Downward who held the title from 1974 to 1988.[89] The current Lord Lieutenant is Warren James Smith.[90] As a geographic county, Greater Manchester is used by the government (via the Office for National Statistics) for the gathering of county-wide statistics, and organising and collating general register and census material.[91]

Bury Town Hall |

Bolton Town Hall |

Manchester Town Hall |

Oldham Civic Centre |

Rochdale Municipal Offices |

Salford Civic Centre |

.jpg) Stockport Town Hall |

Tameside Council Offices |

Trafford Town Hall |

Wigan Civic Centre |

Demography

Greater Manchester has a population of 2,553,800 (as of 2006), making it the third most populous county in the United Kingdom (after Greater London and the West Midlands).[92] It is the seventh most densely populated county of England. The demonym of Greater Manchester is "Greater Mancunian".[93]

Greater Manchester is home to a diverse population and is a multicultural agglomeration with significant ethnic minority population comprising 8.49% of the total population.[94][95] There are currently over 66 refugee nationalities in the county.[96] As of the 2001 UK census, 74.2% of Greater Manchester's residents were Christian, 5.0% Muslim, 0.9% Jewish, 0.7% Hindu, 0.2% Buddhist, and 0.1% Sikh. 11.4% had no religion, 0.2% had an alternative religion and 7.4% did not state their religion. This is similar to the rest of the country, although the proportions of Muslims and Jews are nearly twice the national average.[97] Greater Manchester is covered by the Roman Catholic Dioceses of Salford and Shrewsbury,[98][99] and the Archdiocese of Liverpool. Most of Greater Manchester is part of the Anglican Diocese of Manchester,[100] apart from Wigan which lies within the Diocese of Liverpool.[101]

Following the deindustrialisation of Greater Manchester in the mid-20th century, there was a significant economic and population decline in the region, particularly in Manchester and Salford.[102][103] Vast areas of low-quality squalid terraced housing that were built throughout the Victorian era were found to be in a poor state of repair and unsuited to modern needs; many inner-city districts suffered from chronic social deprivation and high levels of unemployment.[103][104] Slum clearance and the increased building of social housing overspill estates by Salford and Manchester City Councils lead to a decrease in population in central Greater Manchester.[105] During the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, the population of Greater Manchester declined by over 8,000 inhabitants a year.[103] While the population of the City of Manchester shrank by about 40% during this time (from 766,311 in 1931 to 452,000 in 2006), the total population of Greater Manchester only decreased by 8%.[103]

| Population totals for Greater Manchester | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population | ||

| 1801 | 328,609 | 1871 | 1,590,102 | 1941 | 2,693,775 | ||

| 1811 | 409,464 | 1881 | 1,866,649 | 1951 | 2,688,987 | ||

| 1821 | 526,230 | 1891 | 2,125,318 | 1961 | 2,699,711 | ||

| 1831 | 700,486 | 1901 | 2,357,150 | 1971 | 2,729,741 | ||

| 1841 | 860,413 | 1911 | 2,617,598 | 1981 | 2,575,441 | ||

| 1851 | 1,037,001 | 1921 | 2,660,088 | 1991 | 2,569,700 | ||

| 1861 | 1,313,550 | 1931 | 2,707,070 | 2001 | 2,482,352 | ||

| Pre-1974 statistics were gathered from local government areas that now comprise Greater Manchester Source: Great Britain Historical GIS.[106] |

|||||||

Greater Manchester's housing stock comprises a variety of types. Manchester city centre is noted for its high-rise apartments,[107] while Salford has some of the tallest and most densely populated tower block estates in Europe.[108] Throughout Greater Manchester, rows of terraced houses are common, most of them built during the Victorian and Edwardian periods. The Housing Market Renewal Initiative has identified Manchester, Salford, Rochdale and Oldham as areas with terraced housing unsuited to modern needs. Although Greater Manchester has a reputation as an urban sprawl, the county does have areas of green belt. Altrincham, with its neighbours Bowdon and Hale, is said to constitute a "stockbroker belt, with well-appointed dwellings in an area of sylvan opulence".[109]

Education

Greater Manchester has four universities: the University of Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University, University of Salford and the University of Bolton. Together with the Royal Northern College of Music they had a combined population of students in higher education of 101,165 in 2007 – the third highest number in England behind Greater London (360,890) and the West Midlands (140,980),[110] and the thirteenth highest in England per head of population.[111] The majority of students are concentrated on Oxford Road in Manchester, Europe's largest urban higher education precinct.[112]

Primary, secondary and further education within Greater Manchester are the responsibility of the constituent boroughs which form local education authorities and administer schools and colleges of further education. The county is also home to a number of independent schools such as St Bede's College, Manchester Grammar School, Bolton School and Bury Grammar School.

Economy

Much of Greater Manchester's wealth was generated during the Industrial Revolution. The world's first cotton mill was built in the town of Royton,[113][114] and the county encompasses several former mill towns. An Association for Industrial Archaeology publication describes Greater Manchester as "one of the classic areas of industrial and urban growth in Britain, the result of a combination of forces that came together in the 18th and 19th centuries: a phenomenal rise in population, the appearance of the specialist industrial town, a transport revolution, and weak local lordship".[13] Much of the county was at the forefront of textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution and into the early 20th century, represented by the former textile mills found throughout the county.[13]

The territory that makes up Greater Manchester experienced a rapid decline of these traditional sectors, partly during the Lancashire Cotton famine brought on by the American Civil War, but mainly as part of the post-war economic depression and deindustrialisation of Britain that occurred during the 20th century.[103] Considerable industrial restructuring has helped the region to recover.[115] Historically, the docks at Salford Quays were an industrial port, though are now (following a period of disuse) a commercial and residential area which includes the Imperial War Museum North and The Lowry theatre and exhibition centre. A major BBC centre is also scheduled to open there in 2010.[116]

Today, Greater Manchester is the economic centre of the North West region of England and is the largest sub-regional economy in the UK outside London and South East England.[117] Greater Manchester represents more than £42 billion of the UK regional GVA, more than Wales, Northern Ireland or North East England.[118] Manchester city centre, the central business district of Greater Manchester, is a major centre of trade and commerce and provides Greater Manchester with a global identity, specialist activities and employment opportunities; similarly, the economy of the city centre is dependent upon the rest of the county for its population as an employment pool, skilled workforce and for its collective purchasing power.[119] Manchester today is a centre of the arts, the media, higher education and commerce. In a poll of British business leaders published in 2006, Manchester was regarded as the best place in the UK to locate a business.[120] A report commissioned by Manchester Partnership, published in 2007, showed Manchester to be the "fastest-growing city" economically.[121] It is the third most visited city in the United Kingdom by foreign visitors[122] and is now often considered to be the second city of the UK.[123] The Trafford Centre is one of the largest shopping centres in the United Kingdom, and is located within the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford.

As of the 2001 UK census, there were 1,805,315 residents of Greater Manchester aged 16 to 74. The economic activity of these people was 40.3% in full-time employment, 11.3% in part-time employment, 6.7% self-employed, 3.5% unemployed, 5.1% students without jobs, 2.6% students with jobs, 13.0% retired, 6.1% looking after home or family, 7.8% permanently sick or disabled and 3.5% economically inactive for other reasons. The figures follow the national trend, although the percentage of self-employed people is below the national average of 8.3%.[124] The proportion of unemployment in the county varies, with the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport having the lowest at 2.0% and the City of Manchester the highest at 7.9%.[125] In 2001, of the 1,093,385 residents of Greater Manchester in employment, the industry of employment was: 18.4% retail and wholesale; 16.7% manufacturing; 11.8% property and business services; 11.6% health and social work; 8.0% education; 7.3% transport and communications; 6.7% construction; 4.9% public administration and defence; 4.7% hotels and restaurants; 4.1% finance; 0.8% electricity, gas, and water supply; 0.5% agriculture; and 4.5% other. This was roughly in line with national figures, except for the proportion of jobs in agriculture which is only about a third of the national average of 1.5%, due to the overwhelmingly urban, built-up land use of Greater Manchester.[115][126]

| Regional gross value added by the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester at current basic prices. Figures are in millions of British pounds sterling.[127] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Regional Gross Value Added[A] | Agriculture[B] | Industry[C] | Services[D] |

| 1995 | 25,368 | 59 | 8,344 | 16,966 |

| 2000 | 32,995 | 38 | 8,817 | 24,140 |

| 2003 | 38,300 | 48 | 8,973 | 29,279 |

| 2005[128] | 42,082 | — | —— | ——– |

- A Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

- B Includes hunting and forestry

- C Includes energy and construction

- D Includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

Transport

Public transport services in Greater Manchester are co-ordinated by the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (GMPTE), a public body (Passenger Transport Executive) established as SELNEC PTE in 1969 in accordance with the Transport Act 1968.[129] The original SELNEC Passenger Transport Authority was taken over by the Greater Manchester County Council on 1 April 1974 in order to co-ordinate bus and rail services within the new county.[129] The council had overall responsibility for strategic planning and all policy decisions covering public transport and highways. GMPTE's purpose was to secure the provision of a completely integrated and efficient system of passenger transport to meet the needs of its area.[129] In 1977, it was noted as the largest authority for public transport in the United Kingdom after London Transport.[129]

Greater Manchester lies at the heart of the North West transport network. Much of the infrastructure is centred on the City of Manchester with the Manchester Inner Ring Road, an amalgamation of several major roads, circulating the city centre. The county is the only place in the UK to have a fully orbital motorway,[130] the M60, which passes through all of the boroughs except Bolton and Wigan. Greater Manchester has a higher percentage of the motorway network than any other county in the country,[131] and according to the Guinness Book of World Records, it has the most traffic lanes side by side (17), spread across several parallel carriageways (M61 at Linnyshaw in Walkden, close to the M60 interchange).[132] Greater Manchester's 85 miles (137 km) of motorway network saw 5.8 billion vehicle kilometres in 2002 – about 6% of the UK's total, or 89,000 vehicles a day.[130] The A580 "East Lancs" road is a primary A road that connects Manchester and Salford with Liverpool. It was the UK's first purpose-built intercity highway and was officially opened by King George V on 18 July 1934.[133] Throughout 2008, there were proposals for congestion charging in Greater Manchester.[134][135] Unlike the London scheme, two cordons would have been used, one covering the main urban core of the Greater Manchester Urban Area and another covering Manchester city centre.[136]

There is an extensive bus network which radiates from Manchester city centre. The largest providers are First Manchester for the northern parts of the county and Stagecoach Manchester for the southern parts. In addition to the network of bus routes, a light rail system began operating in 1992 called Manchester Metrolink. The tram system serves the City of Manchester, City of Salford, Bury and Trafford. An expansion of the system is due to begin in 2008 which should in time see the system run to all boroughs except Bolton and Wigan. Greater Manchester has a rail network of 142 route miles (229 km) with 98 stations, forming a central hub to the North West rail network.[137] Train services are provided by private operators and run on the national rail network which is owned and managed by Network Rail. An extensive canal network also remains from the Industrial Revolution.

Manchester Airport, which is the fourth busiest in the United Kingdom, serves the county and wider region with flights to more worldwide destinations than any other airport in the UK.[138] Since June 2007 it has served 225 routes.[139] The airport handled 21.06 million passengers in 2008.

The three modes of public surface transport in the area are heavily used. 19.7 million rail journeys were made in the GMPTE-supported area in the 2005/2006 financial year – an increase of 9.4% over 2004/2005; there were 19.9 million journeys on Metrolink; and the bus system carried 219.4 million passengers.[138]

Sports

Manchester hosted the 2002 Commonwealth Games which was, at a cost of £200M for the sporting facilities and a further £470M for local infrastructure, by far the biggest and most expensive sporting event held in the UK and the first to be an integral part of urban regeneration.[140] A mix of new and existing facilities were used. New amenities included the Manchester Aquatics Centre, Bolton Arena, the National Squash Centre, and the City of Manchester Stadium. The Manchester Velodrome was built as part of the bid to hold the 2000 Olympic Games.[141] After the Commonwealth Games the City of Manchester Stadium was converted for football use, and the adjacent warm-up track upgraded to become the Manchester Regional Arena.[142] Other facilities continue to be used by elite athletes.[140] The net amount of regeneration to the area is not easy to quantify. Cambridge Policy Consultants estimate 4,500 full-time jobs as a direct consequence, and Grattan points to other long-term benefits accruing from publicity and the improvement of the area's image.[140]

In football, four Greater Manchester teams will play in the 2008–09 Premier League. Manchester United F.C. are one of the world's best-known football teams, and in April 2008 Forbes estimated that they were also the world's richest club.[143] They are the current Carling Cup champions, have won the league championship eighteen times, the FA Cup a record eleven times and have been European champions three times.[144] Their Old Trafford ground has hosted the FA Cup Final and international matches. Manchester City F.C. moved from Maine Road to the City of Manchester Stadium after the 2002 Commonwealth Games. They have won the league championship twice and the FA Cup four times.[145][146] Bolton Wanderers F.C. have won the FA cup four times.[145] Wigan Athletic F.C. are one of the league's younger sides, and have yet to win a major title.[147] In addition, Oldham Athletic A.F.C. and Stockport County F.C., will play in League One; Bury F.C. (two FA Cup wins) and Rochdale A.F.C. will play in League Two.

In rugby league, the Wigan Warriors and the Salford City Reds compete in the Super League; Wigan have won the Super League/Championship eighteen times, the Challenge Cup seventeen times, and the World Club Challenge three times.[148] Leigh Centurions and the Rochdale Hornets take part in National League One, with Oldham Roughyeds and local rivals Swinton Lions in National League Two.

In rugby union, Stockport's Sale Sharks compete in the Guinness Premiership, and won the league in 2006.[149] Whitefield based Sedgley Park RUFC compete in National Division One, Manchester RUFC in National Division Two and Wigan side Orrell RUFC in National Division Three North.

Lancashire County Cricket Club began as Manchester Cricket Club and represents the (historic) county of Lancashire. Lancashire contested the original 1890 County Championship. The team has won the County Championship eight times, and in 2007 finished third, narrowly missing their first title since 1950.[150] Their Old Trafford ground, near the football stadium of the same name, regularly hosts test matches. Possibly the most famous took place in 1956, when Jim Laker took a record nineteen wickets in the fourth test against Australia.[151] Cheshire County Cricket Club are a minor counties club who sometimes play in the south of the county.[152]

The Kirkmanshulme Lane stadium in Belle Vue is the home to top-flight speedway team the Belle Vue Aces and regular greyhound racing. Professional ice hockey returned to the area in early 2007 with the opening of a purpose-designed rink in Altrincham, the Altrincham Ice Dome, to host the Manchester Phoenix. Their predecessor, Manchester Storm, went out of business in 2002 due to financial problems which led to them being unable to pay players' wages or the rent for the Manchester Evening News Arena in which they played.[153][154]

Horse racing has taken place at several sites in the county. The two biggest courses were both known as Manchester Racecourse – though neither was within the boundaries of Manchester – and ran from the 17th century until 1963. Racing was at Kersal Moor until 1847 when the racecourse at Castle Irwell was opened. In 1867 racing was moved to New Barnes, Weaste, until the site was vacated (for a hefty price) in 1901 to allow an expansion to Manchester Docks. The land is now home to Dock 9 of the re-branded Salford Quays. Racing then moved back to Castle Irwell which later staged a Classic – the 1941 St. Leger – and was home to the Lancashire Oaks (nowadays run at Haydock Park) and the November Handicap, which was traditionally the last major race of the flat season. Through the late 50s and early 60s the track saw Scobie Breasley and Lester Piggott annually battle out the closing acts of the jockey's title until racing ceased on 7 November 1963.[155]

Athletics takes place at the Regional Athletics Arena in Sportcity, which has hosted numerous national trials, Robin Park in Wigan, Longford Park in Stretford (home to Trafford Athletic Club), Woodbank Stadium in Stockport (home to Stockport Harriers) and the Cleavleys Track in Winton (home to Salford Harriers). As of 2008, new sports facilities including a 10,000 capacity stadium and athletics venue are being constructed at Leigh Sports Village.[156]

Culture

Art, tourism, culture and sport provide 16% of employment in Greater Manchester. The proportion is highest in Manchester.[157]

Greater Manchester has the highest number of theatre seats per head of population outside London. Most, if not all, of the larger theatres are subsidised by local authorities or the North West Regional Arts Board.[158] The Royal Exchange Theatre formed in the 1970s out of a peripatetic group staging plays at venues such as at the University [of Manchester] Theatre and the Apollo Theatre. A season in a temporary stage in the former Royal Exchange, Manchester was followed by funding for a theatre in the round, which opened in 1976.[159] The Lowry houses two theatres, used by travelling groups in all the performing arts.[157][160] The Opera House is a 1,900-seat venue hosting travelling productions, often musicals just out of the West End.[161] Its sister venue, The Palace, hosts generally similar shows. The Oldham Playhouse, one of the older theatres in the region, helped launch the careers of Stan Laurel and Charlie Chaplin. Its productions are described by the 2007 CityLife guide as 'staunchly populist' – and popular.[161] There are many other venues scattered throughout the county, of all types and sizes.[161]

Art galleries in the county include: Gallery Oldham, which has in the past featured work by Pablo Picasso;[162] The Lowry at Salford Quays, which has a changing display of L. S. Lowry's work alongside travelling exhibitions; Manchester Art Gallery, a major provincial art gallery noted for its collection of Pre-Raphaelite art and housed in a Grade I listed building by Charles Barry;[163] Salford Museum and Art Gallery, a local museum with a recreated Victorian street;[164] and Whitworth Art Gallery, a broad-based gallery now run by the University of Manchester.

Greater Manchester has four professional orchestras, all based in Manchester. The Hallé Orchestra is the UK's oldest extant symphony orchestra (and the fourth oldest in the world),[165] supports a choir and a youth orchestra, and releases its recordings on its own record label.[166] The Hallé is based at the Bridgwater Hall but often tours, typically giving 70 performances "at home" and 40 on tour.[166] The BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, one of five BBC orchestras, can trace its history back to the early days of radio broadcasting in 1926.[167] As of 2008 it is based at the BBC's Oxford Road studios,[168] but is expected to move to MediaCityUK in Salford.[169] The Manchester Camerata and the Northern Chamber Orchestra are smaller, though still professional, organizations.[170] The main classical venue is the 2,341-seat Bridgewater Hall in Manchester, opened in 1996 at a cost of £42M.[171] Manchester is also a centre for musical education, via the Royal Northern College of Music and Chetham's School of Music.[172]

The main popular music venue is the Manchester Evening News Arena, next to Victoria station. It seats over 21,000, is the largest indoor arena in Europe, has been voted International Venue of the Year, and for several years was the most popular venue in the world.[173] The sports grounds in the county also host some of the larger pop concerts.[174]

Some of Greater Manchester's museums showcase the county's industrial and social heritage. The Hat Works in Stockport is the UK's only museum dedicated to the hatting industry; the museum moved in 2000 to a Grade II listed Victorian mill, previously a hat factory.[175] The Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester, amongst other displays, charts the rise of science and industry and especially the part Manchester played in its development; the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council described the displays as "pre-eminent collections of national and international importance".[176] Urbis began its life as a museum of the modern city, which attempted to explain the effects and experiences of life in the city. It was then transformed into an exhibition centre, which had its most successful year in 2006. Urbis is now preparing to enter its third phase since opening in 2002, as the National Football Museum.[177] Stockport Air Raid Shelters uses a mile of underground tunnels, built to accommodate 6,500 people, to illustrate life in the Second World War's air raid shelters.[178] The Imperial War Museum North in Trafford Park is one of the Imperial War Museum's five branches. Alongside exhibitions of war machinery are displays describing how people's lives are affected by war.[179] The Museum of Transport in Manchester, which opened in 1979, has one of the largest collections of vehicles in the country.[180] The People's History Museum is "the national centre for the collection, conservation, interpretation and study of material relating to the history of working people in Britain"; the museum is closed for redevelopment and will reopen in 2009.[181] The Pankhurst Museum is based in the early feminist Emmeline Pankhurst's former home and includes a parlour laid out in contemporary style.[182] Manchester United, Manchester City, and Lancashire CCC all have dedicated museums illustrating their histories. Wigan Pier, best known from George Orwell's book The Road to Wigan Pier,[183] was the name of a wharf on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in Wigan. The name has been reused to describe an industrial-based visitor attraction, partly closed for redevelopment as of 2008.[184]

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in Greater Manchester

- Grade II* listed buildings in Greater Manchester

- Greater Manchester Employer Coalition

- List of companies based in Greater Manchester

- List of people from Greater Manchester

References

Notes

- ↑ Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. "Local Government Finance Statistics England No.16". local.odpm.gov.uk. http://www.local.odpm.gov.uk/finance/stats/lgfs/2005/lgfs16/h/lgfs16/annex_a.html. Retrieved on 21 February 2008.

- ↑ Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. "Greater Manchester Fire Service". stockport.gov.uk. Archived from the original on March 3, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080303043751/http://www.stockport.gov.uk/content/advicebenefitsemergencies/emergencyservices/gmfire/?a=5441. Retrieved on 6 March 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Office for National Statistics. "Gazetteer of the old and new geographies of the United Kingdom" (PDF). statistics.gov.uk. p. 48. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/downloads/ons_geography/Gazetteer_v3.pdf. Retrieved on 6 March 2008.

•Office for National Statistics (17 September 2004). "Beginners' Guide to UK Geography: Metropolitan Counties and Districts". statistics.gov.uk. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/geography/metropolitan.asp. Retrieved on 6 March 2008.

•"North West – Electoral Commission". The Electoral Commission. http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/boundary-reviews/all-reviews/north-west. Retrieved on 7 July 2008. - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Greater Manchester Gazetteer". Greater Manchester County Record Office. Places names - G to H. http://www.gmcro.co.uk/Guides/Gazeteer/gazzg.htm. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ↑ Nevell and Redhead (2005), p. 20.

- ↑ Adrian Morris. "Roman Wigan". Wigan Archaeological Society. http://www.wiganarchsoc.co.uk/how.html#Roman. Retrieved on 10 July 2008.

- ↑ Bayliss (1996), p. 6.

- ↑ "Mamucium Roman fort". Pastscape.org.uk. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=76731. Retrieved on 29 December 2007.

- ↑ "Castle Shaw". Pastscape.org.uk. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=45891. Retrieved on 29 December 2007.

- ↑ Redhead, Norman, in: Hartwell, Hyde and Pevsner (2004), p. 18.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. ix.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), pp. 24–25.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 McNeil and Nevell (2000), pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Aspin (1981), p. 3.

- ↑ Cowhig (1976), pp. 7–9.

- ↑ Kidd (2006), pp. 12, 15–24, 224.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hall, Peter (1998). "The first industrial city: Manchester 1760–1830". Cities in Civilization. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-84219-6.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Frangopulo (1977), p. 226.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 268.

- ↑ Swarbrick, J., (February 1914), Greater Manchester: The Future Municipal Government of Large Cities, pp. 12–15.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 229.

- ↑ Dearlove, John (1979). The reorganisation of British local government: old orthodoxies and a political perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29456-8.

- ↑ Clark 1973, p. 1.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Frangopulo (1977), p. 227.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Frangopulo (1977), p. 228.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 231.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 234.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Redcliffe-Maud et al. (June 1969), pp. 219–235.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 233.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 264.

- ↑ The SELNEC Preservation Society. "The Formation of the SELNEC PTE". selnec.org.uk. http://www.selnec.org.uk/selnec.htm. Retrieved on 6 July 2008.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Redcliffe-Maud and Wood (1975), pp. 46–7, 56, 157.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 6 July 1972 , columns 763–834

- ↑ "Lancashire saved from 'Botchdale'". The Times. 7 July 1972.

- ↑ "Philosophy on councils has yet to emerge". The Times. 8 July 1972.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 HMSO. Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70

- ↑ At 31 March 1974, Ringway was a civil parish in the Bucklow Rural District.

- ↑ "British Local Election Database, 1889–2003". AHDS – Arts and Humanities data service. 28 June 2006. http://ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/collection.htm?uri=hist-5319-1. retrieved on 5 March 2008.

- ↑ "All change in local affairs". The Times. 1 April 1974.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. xii.

- ↑ Clark 1973, p. 101.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 246.

- ↑ Bristow & Cross 1983, p. 30.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), pp. 246–255.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Wannop 2002, pp. 144–145.

- ↑ Parkinson-Bailey (2000), pp. 214–5.

- ↑ Taylor, Evans & Fraser 1996, p. 76.

- ↑ "Changes in local government units may cause some famous names to disappear". The Times. 2 January 1973.

•"Post Office will ignore some new counties over addresses". The Times. 26 November 1973. - ↑ Address Management Guide. Royal Mail. 2004.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Wilson & Game 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Walker, David (15 January 1983). "Tory plan to abolish GLC and metropolitan councils, but rates stay". The Times.

•Haviland, Julian (5 May 1983). "Tories may abolish county councils if they win election". The Times.

•Tendler, Stewart (16 June 1983). "Big cities defiant over police". The Times. - ↑ "Angry reaction to councils White Paper". The Times. 8 October 1983.

- ↑ Wilson & Game 2002, p. 62.

- ↑ Association of Greater Manchester Authorities. "About AGMA". agma.gov.uk. http://www.agma.gov.uk/ccm/navigation/about-agma/. Retrieved on 5 March 2008.

- ↑ BISER Europe Regions Domain Reporting (2003). "Regional Portrait of Greater Manchester - 5.1 Spatial Structure" (PDF). biser-eu.com. http://www.biser-eu.com/regions/Greater%20Manchester.pdf. Retrieved on 17 February 2007.

- ↑ HMSO. Lieutenancies Act 1997. 1997 c.23.

- ↑ Wood, Edward (11 December 1998). Research Paper 98/115 –The Greater London Authority Bill: A Mayor and Assembly for London – Bill 7 of 1998–99. London: House of Commons Library. http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/rp98/rp98-115.pdf.

- ↑ HM Treasury (17 July 2007). "Sub-national economic development and regeneration review". hm-treasury.gov.uk. http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/spending_review/spend_csr07/reviews/subnational_econ_review.cfm. Retrieved on 28 February 2008.

- ↑ Fairley, Peter (18 January 2008). "Comment – A faster track for the city-regions". publicfinance.co.uk. http://www.publicfinance.co.uk/features_details.cfm?News_id=32036. Retrieved on 28 February 2008.

- ↑ Ottewell, David (25 June 2008). "Now YOU can vote on congestion charge". Manchester Evening News: pp. 1–2.

- ↑ "More than the sum of their parts - partnerships seal deal to increase economic growth". communities.gov.uk. 14 July 2008. Archived from the original on August 3, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080803231324/http://www.communities.gov.uk/news/corporate/892523. Retrieved on 16 July 2008.

- ↑ "Date set for C-charge referendum". news.bbc.co.uk. 2008-09-29. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/manchester/7588142.stm. Retrieved 5 January 2010. Retrieved on 5 August 2008.

- ↑ Sturcke, James (12 December 2008). "Manchester says no to congestion charging". London: guardian.co.uk. http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2008/dec/12/congestioncharging-transport. Retrieved on 12 December 2008.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (2009). "City Region Governance: A consultation on future arrangements in Greater Manchester" (PDF). agma.gov.uk. http://www.agma.gov.uk/cms_media/files/agma_city_region_governance_final.pdf. Retrieved on 18 March 2010.

- ↑ Association of Greater Manchester Authorities. "City Region". agma.gov.uk. http://www.agma.gov.uk/city_region/index.html. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ HM Treasury (2009-12-16). "Greater Manchester granted city region status". hm-treasury.gov.uk. http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/press_122_09.htm. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- ↑ "John Denham - Greater Manchester to be country's first ever Combined Authority". communities.gov.uk. 2010-03-31. http://www.communities.gov.uk/news/corporate/1527485. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ↑ "Plan to end rail and road misery". thisislancashire.co.uk. 2010-03-31. http://www.thisislancashire.co.uk/news/5953132.Plan_to_end_rail_and_road_misery/. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester to become first 'city region'". Oldham Advertiser. oldhamadvertiser.co.uk. 2010-03-29. http://www.oldhamadvertiser.co.uk/news/s/1202108_greater_manchester_to_become_first_city_region. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester agrees to combined authority". Manchester City Council. 29 March 2010. http://www.manchester.gov.uk/news/article/5429/greater_manchester_agrees_to_combined_authority. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Dawson (1992), Chapter 6: The County Tops.

- ↑ Salford City Council (2007). "Chat Moss". salford.gov.uk. http://www.salford.gov.uk/living/planning/naturalenvironment/landscape/chatmoss.htm. Retrieved on 13 November 2007.

•"Agricultural Land Classification" (PDF). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. July 2003. http://www.defra.gov.uk/farm/environment/land-use/pdf/alcleaflet.pdf. Retrieved on 12 July 2008. - ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority. "The Greater Manchester Area and its Regional Context". gmltp.co.uk. http://www.gmltp.co.uk/gmltp2_html/section_123173639918.html. Retrieved on 11 April 2007.

- ↑ State of the English Cities: Volume 1 Produced for the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, (2006). Online Report Accessed 17 December 2006.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "Manchester Airport 1971–2000 weather averages". Met Office. 2001. http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/averages/19712000/sites/manchester_airport.html. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "UK 1971–2000 averages". Met Office. 2001. http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/averages/19712000/areal/uk.html. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- ↑ Met Office (2007). "Annual UK weather averages". Met Office. http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/averages/19712000/areal/uk.html. Retrieved on 23 April 2007.

- ↑ "Roads chaos as snow sweeps in Manchester". Manchester Evening News. 2005. http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/147/147321_roads_chaos_as_snow_sweeps_in.html. Retrieved on 15 July 2007.

- ↑ "Peak District sightseer's guide – Snake Pass". High Peak. 2002. http://www.highpeak.co.uk/hp/h_snakbd.htm. Retrieved on 6 July 2007.

- ↑ "Icy conditions hit the UK after days of heavy snow". BBC News. news.bbc.co.uk. 2010-01-07. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/8444862.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-07

- ↑ "Lib Dems close in on Manchester". Manchester Evening News. 11 June 2004. http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/119/119942_lib_dems_close_in_on_manchester.html. Retrieved on 26 February 2006.

- ↑ "Labour party returns to Manchester". timeout.com. 2006. http://www.timeout.com/manchester/feature/2009/4/Labour_party_returns_to_Manchester.html#articleAfterMpu. Retrieved on 26 February 2008.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Frangopulo (1977), p. 138.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Barlow, Max (1995). "Greater Manchester: conurbation complexity and local government structure". Political Geography 14 (4): 379–400. doi:10.1016/0962-6298(95)95720-I.

- ↑ Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council (N.D.), p. 65.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester Local Transport Plan". Greater Manchester Local Transport Plan website. http://www.gmltp.co.uk. Retrieved on 12 December 2006.

- ↑ Hebbert, Michael; Iain Deas (2000). "Greater Manchester – 'up and going'?". Policy & Politics 28 (1): 79–92. ISSN 5736 0305 5736.

- ↑ Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. "Keeper of the Rolls". duchyoflancaster.co.uk. http://www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk/output/page61.asp. Retrieved on 8 July 2008.

- ↑ The Lord-Lieutenants Order 1973 (1973/1754)

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 58395, p. 10329, 18 July 2007.

- ↑ A Vision of Britain through time. "Greater Manchester Met. C". http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit_page.jsp?u_id=10056925&c_id=10001043. Retrieved on 6 April 2007.

- ↑ "T 09: Quinary age groups and sex for local authorities in the UK; estimated resident population Mid-2006 Population Estimates". National Statistics. 30 May 2008. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/ssdataset.asp?vlnk=9666&More=Y. Retrieved on 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Clark 1973, p. 93.

- ↑ "Regional Portrait of Greater Manchester - 5.3 Population Structure/Migration (demography)" (PDF). BISER Europe Regions Domain Reporting. 2003. http://www.biser-eu.com/regions/Greater%20Manchester.pdf. Retrieved on 18 February 2008.

- ↑ "Warren Smith welcomes you to the Greater Manchester Lieutenancy". manchesterlieutenancy.org. http://www.manchesterlieutenancy.org/. Retrieved on 8 July 2008.

- ↑ "Exodus: The Facts". can.uk.com. 2003. http://www.can.uk.com/exodus/exodus_about.htm. Retrieved on 27 February 2008.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester (health authority) religion". Statistics.gov.uk. http://neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadTableView.do?a=3&b=789833&c=M7+4FU&d=14&e=16&g=353838&i=1x1003x1004&o=1&m=0&r=0&s=1201894343750&enc=1&dsFamilyId=95. Retrieved on 1 February 2008.

- ↑ "Catholic Diocese of Shrewsbury". Dioceseofshrewsbury.org. http://www.dioceseofshrewsbury.org. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "Parishes of the Diocese". Salforddiocese.org.uk. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070502121806/http://www.salforddiocese.org.uk/parishes/masstimes.html. Retrieved on 7 May 2007.

- ↑ "The Church of England Diocese of Manchester". Manchester.anglican.org. http://www.manchester.anglican.org/default.asp. Retrieved on 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Diocese of Liverpool". Liverpool.anglican.org. http://www.liverpool.anglican.org. Retrieved on 1 February 2008.

- ↑ "Market Renewal: Manchester Salford Pathfinder" (PDF). Audit Commission. 2003. http://www.audit-commission.gov.uk/Products/BVIR/9AC95DA0-C6A1-4b9b-9A0D-D305DE72FFC8/ManchesterSalford.pdf. Retrieved on 22 February 2008.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 103.3 103.4 "Shrinking Cities: Manchester/Liverpool II" (PDF). shrinkingcities.com. March 2004. p. 36. http://shrinkingcities.com/fileadmin/shrink/downloads/pdfs/WP-II_Manchester_Liverpool.pdf. Retrieved on 4 March 2008.

- ↑ Cooper (2005), p. 47.

- ↑ Shapely, Peter (2002–3). "The press and the system built developments of inner-city Manchester" (PDF). Manchester Region History Review (Manchester: Manchester Centre for Regional History) 16: 30–39. ISSN 0952-4320. http://www.mcrh.mmu.ac.uk/pubs/pdf/mrhr_16_shapely.pdf. Retrieved on 22 November 2007.

- ↑ A Vision of Britain through time. "Greater Manchester Met. C: Total Population". http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/data_cube_table_page.jsp?data_theme=T_POP&data_cube=N_TPop&u_id=10056925&c_id=10001043&add=N. Retrieved on 6 April 2007.

- ↑ Yakub Qureshi (24 November 2004). "Manchester – Features – A cut above: high rise living is back". bbc.co.uk. http://www.bbc.co.uk/manchester/content/articles/2004/11/24/high_rise_living_hys_feature.shtml. Retrieved on 25 February 2008.

- ↑ Cunningham, John (28 February 2001). "Tower blocks to make a comeback". The Guardian (London: Guardian News and Media Limited). http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2001/feb/28/housingpolicy.keyworkerhousing. Retrieved on 26 February 2008.

- ↑ Frangopulo (1977), p. 224.

- ↑ "Table 0a – All students by institution, mode of study, level of study, gender and domicile 2006/07" (XLS). Students and Qualifiers Data Tables. Higher Education Statistics Agency. 2008. http://www.hesa.ac.uk/dox/dataTables/studentsAndQualifiers/download/institution0607.xls. Retrieved on 21 March 2008.

- ↑ Tight, Malcolm (July 2007). "The (Re)Location of Higher Education in England (Revisited)". Higher Education Quarterly 61 (3): 250–265. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2273.2007.00354.x.

- ↑ Hartwell (2001), p. 105.

- ↑ "Oldham's Economic Profile – Innovation and Technology". Oldham MBC web pages. Oldham Council. http://www.oldham.gov.uk/working/economic_profile/innovation_technology.htm. Retrieved on 27 October 2006.

- ↑ "NW Cotton Towns Learning Journey". Spinning the web. Manchester City Council. http://www.spinningtheweb.org.uk/journey.php?Title=NW+Cotton+towns+learning+journey&step=2&theme=places. Retrieved on 27 October 2006.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 "Regional Portrait of Greater Manchester - 6 Economic Factors" (PDF). BISER Europe Regions Domain Reporting. 2003. http://www.biser-eu.com/regions/Greater%20Manchester.pdf. Retrieved on 17 February 2007.

- ↑ Ian Wylie (2006). "Salford bid wins BBC move north". Manchester Evening News. http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/215/215813_salford_bid_wins_bbc_move_north.html. Retrieved on 5 March 2008.

- ↑ "Manchester city region – Economic Overview". investinmanchester.com. http://www.investinmanchester.com/MarketIntelligence/EconomicOverview/. Retrieved on 30 May 2008.

- ↑ "Greater Manchester Economic Data". Midas Manchester. 2003. http://web.archive.org/web/20070813023005/http://www.investinmanchester.com/be_econ. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved on 10 July 2008.

- ↑ "The Greater Manchester Strategy: Foreword". gmep.org.uk. 2004. Archived from the original on April 22, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080422142422/http://www.gmep.org.uk/ccm/navigation/the-greater-manchester-strategy/. Retrieved on 9 July 2008.

- ↑ "Britain's Best Cities 2005–2006 Executive Summary" (PDF). OMIS Research. 2006. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080226223837/http://www.omis.co.uk/Downloads/BBC06.pdf. Archived from the original on 17 May 2006. Retrieved on 17 July 2008.

- ↑ Retrieved on 30 May 2008."Manchester – The State of the City". Manchester City Council. 2007. http://www.manchester.gov.uk/site/scripts/news_article.php?newsID=2915. Retrieved on 11 September 2007.

- ↑ Marketing Manchester (17 September 2007). "International Visitors To Friendly Manchester Up 10%". Press release. http://www.marketingmanchester.com/news/newsdetails.xsql?id=258. Retrieved on 17 July 2008.

- ↑ "Manchester 'England's second city'". BBC. 12 September 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/2253035.stm. Retrieved 5 January 2010. Retrieved on 2 May 2007.

• "Manchester 'England's Second City'". Ipsos MORI. 2002. http://www.ipsos-mori.com/content/manchester-englands-second-city.ashx. Retrieved on 30 May 2008.

• Riley, Catherine (8 July 2005). "Can Birmingham halt its decline?". The Times (London). http://property.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/property/article541043.ece. Retrieved 31 March 2010. Retrieved on 1 August 2007.

• "Manchester 'close to second city'". BBC. 29 September 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/manchester/4293814.stm. Retrieved 5 January 2010. Retrieved on 2 May 2006.

• "Manchester tops second city poll". BBC. 10 February 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/6349501.stm. Retrieved 5 January 2010. Retrieved on 18 June 2007.

• "Birmingham loses out to Manchester in second city face off". BBC. 2007. http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/pressreleases/stories/2007/02_february/09/birmingham.shtml. Retrieved on 18 June 2007. - ↑ "Greater Manchester (health authority) economic activity". Statistics.gov.uk. http://www.neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk/dissemination/LeadTableView.do?a=7&b=789833&c=Greater+Manchester&d=81&e=16&g=352906&i=1001x1003x1004&m=0&r=1&s=1202045463826&enc=1&dsFamilyId=107. Retrieved on 3 February 2008.

- ↑ "Promoting a Dynamic Economy". Greater Manchester e-Government Partnership. Archived from the original on January 12, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080112085728/http://www.gmep.org.uk/ccm/content/agma/promoting-a-dynamic-economy.en;jsessionid=64C7688F205BEE012F17A5E3001818D5. Retrieved on 12 December 2007.